Proposal for the Restructuring of

the Trieste Social Club

Architecture, Heritage

the Trieste Social Club

Architecture, Heritage

Preamble

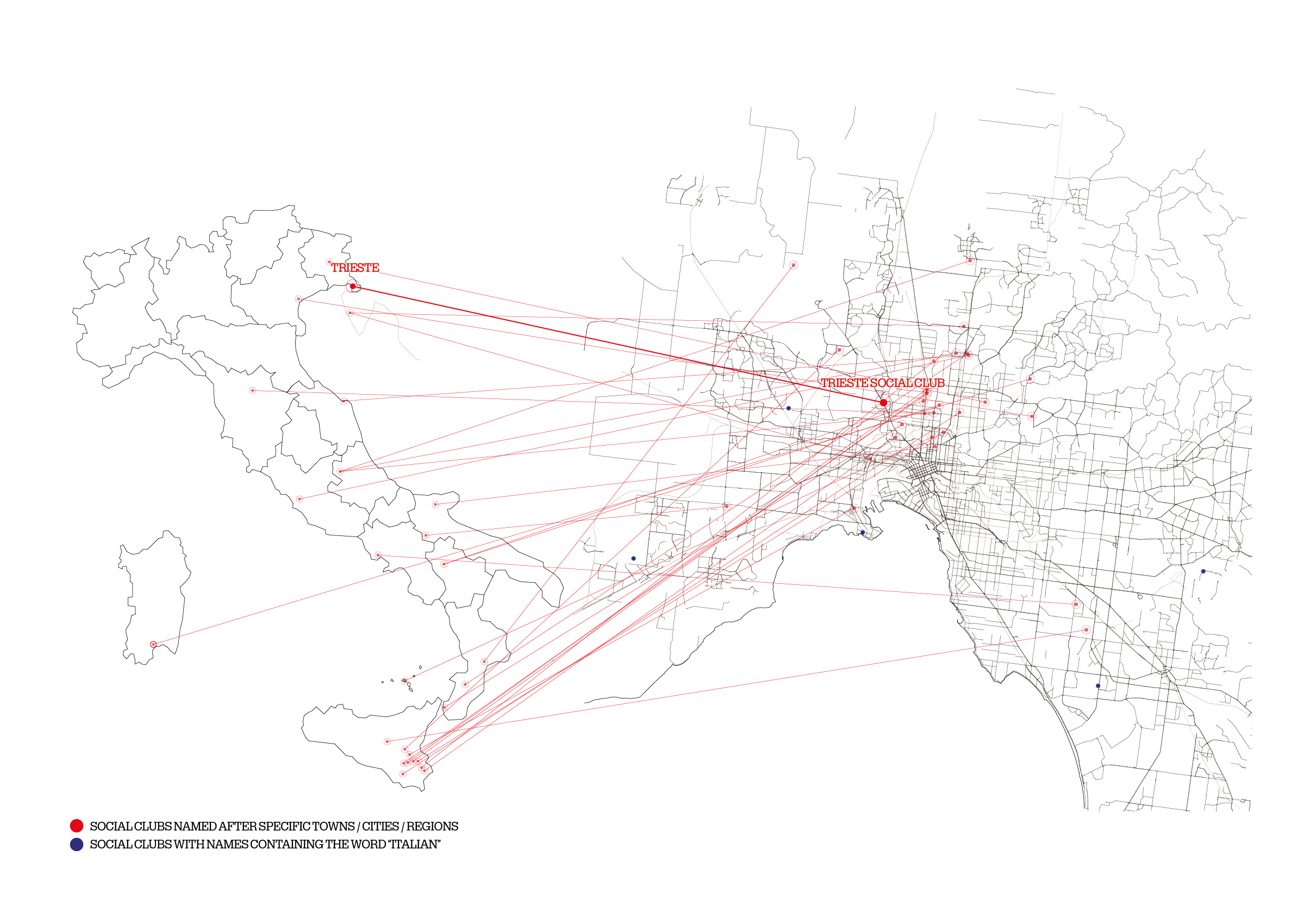

This thesis explores the restructuring of the Trieste Social Club in Essendon, Melbourne, focusing on its role in preserving Triestine migrant identity. Italo-Australian social clubs, once essential social infrastructure for post-war migrants, now face challenges due to ageing populations and shifting identities.

To frame this exploration, I addressed two key research questions:

1. How does migration influence placemaking and the built environment, particularly in the context of Italo-Australian social clubs like the Trieste Social Club?

2. In what ways can the architecture of the Trieste Social Club reflect and facilitate the complex narratives of place-identity and identity politics among migrant communities?

Restructuring

The project introduces “restructuring” as a method distinct from adaptive reuse. While adaptive reuse repurposes buildings for new uses, restructuring favours the reinterpretation of material, programmatic, and compositional structures.

Through processes of excavation, evaluation, and stratification, the project aims to respect the club’s history while adapting it for contemporary needs. Through this approach, the Trieste Social Club can continue to serve as a centre for cultural production, supporting intergenerational connections and evolving demographics.

4 Willow Street, Essendon

The Trieste Social Club, established by immigrants from Trieste—a mitteleuropean city on the eastern edge of northern Italy—serves as a focal point for this investigation into migration, expressions of place-identity, nostalgia, and cultural heritage in the built environment. By restructuring rather than reusing, renovating, or restoring the site, its historical and cultural layers are kept relevant for contemporary and future needs.

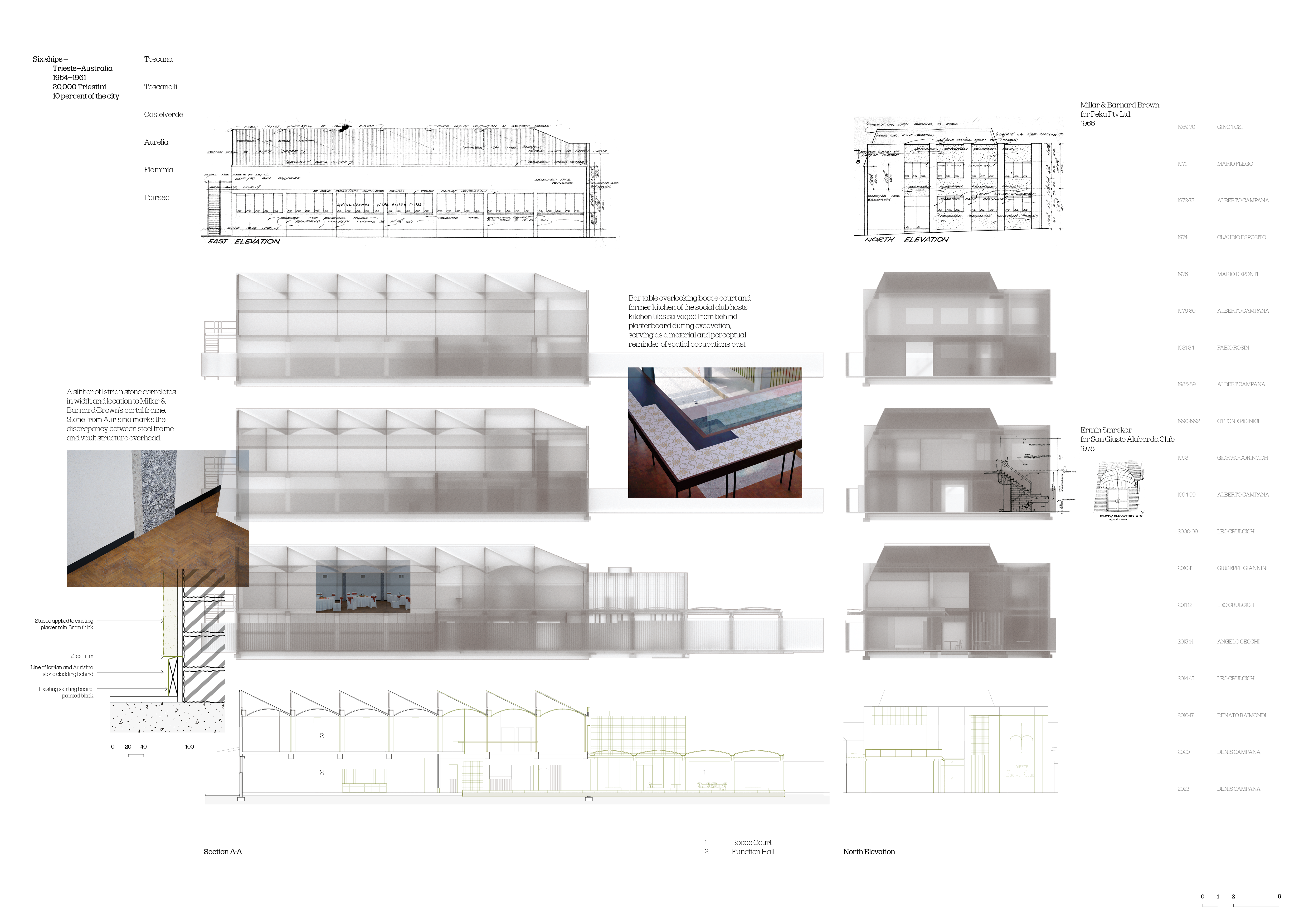

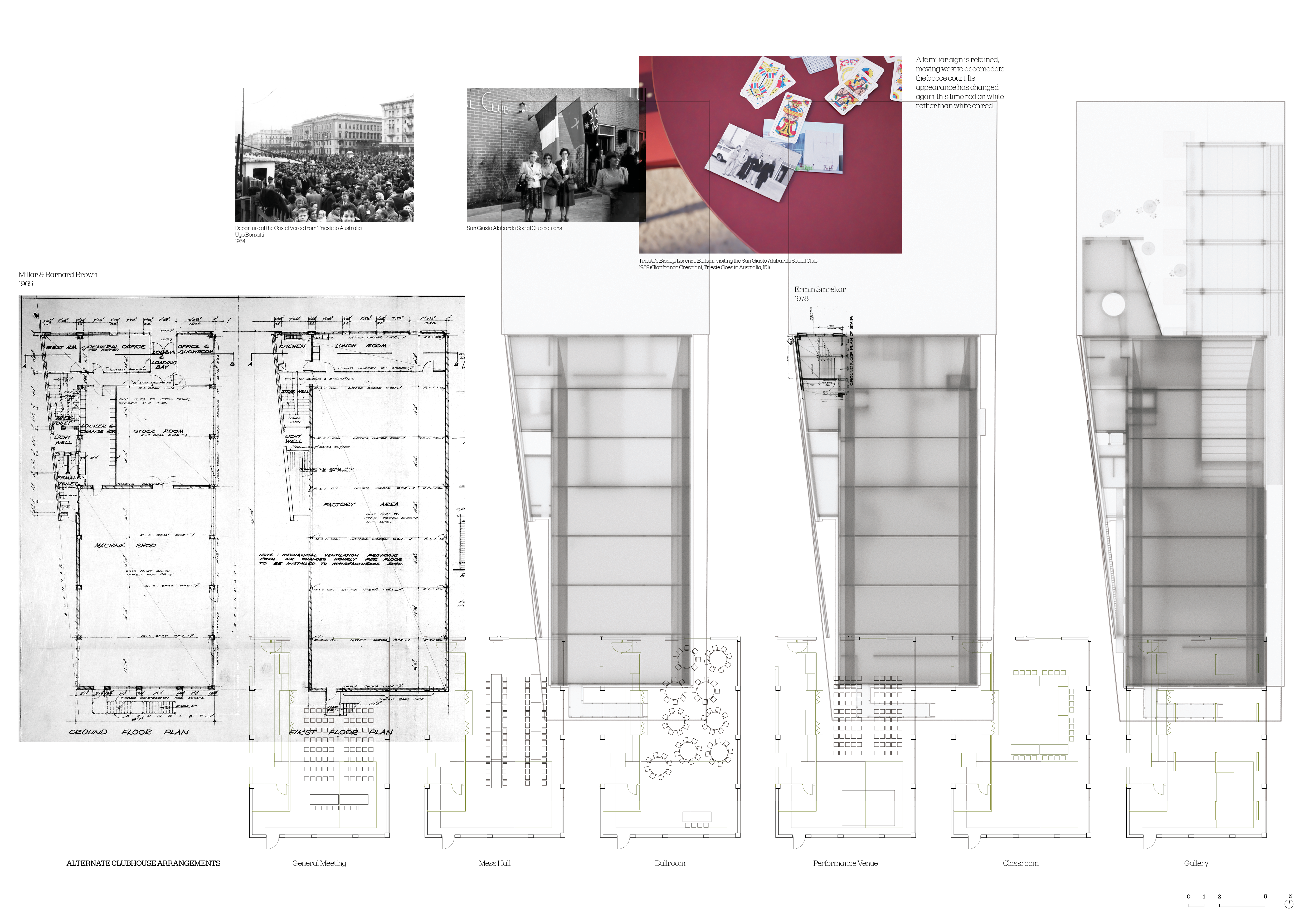

Designed by architects Millar and Barnard-Brown in 1965, the building originally served as a textiles factory. Post-Second World War immigration saw the establishment of various social clubs to support Italian immigrants in Melbourne’s suburbs. The then-San Giusto Alabarda Social Club purchased this factory in 1978 and adapted it under the guidance of Trieste-born RMIT-trained architect Ermin Smrekar. A significant adaptation at this time was the infilling of the sawtooth volume with a vaulted structure, converting the expansive, light-filled factory floor into a ballroom.

Proposed Design

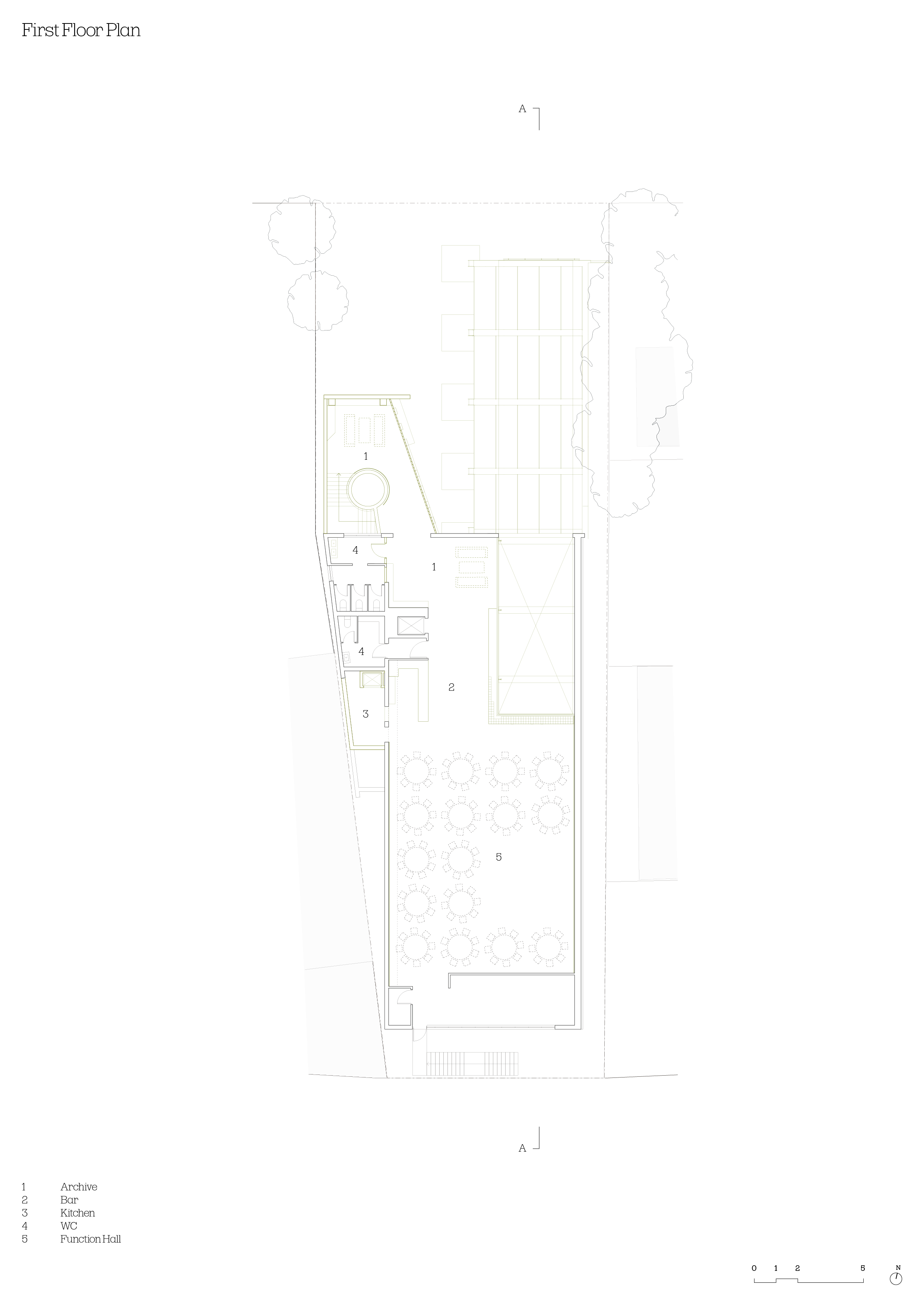

Aligned with these processes of excavation, evaluation, and stratification, the proposal consists of a series of interventions for the existing site - three in particular exemplify these distinct attitudes to space-time relations.

Firstly, I propose the creation of a bocce court. Extending into the building's facade this gesture displaces the existing kitchen, which is subsequently pivoted around the ground floor clubhouse and tucked into the building’s side. The court’s canopy sits atop columns spaced 4200 apart following structural and rhythmic cues from Millar & Barnard Brown’s building. These columns are covered in a basalt roughcast, a similar but different expression to the factory’s facade. The bocce court reflects the club’s Italo-Australian context while offering an intergenerational and casual recreational space for members and the broader neighbourhood. Its presence transforms the former interior walls of the social club’s kitchen into partial exterior and disrupts its new adjacencies. Upstairs a bar overlooks the court. Hosting kitchen tiles salvaged from behind plasterboard during excavation, the bar’s expression serves as material and perceptual reminders of spatial occupations past.

Secondly, an outbuilding extending from the facade’s west fosters moments of encounter and reflection. The outbuilding hosts a cafe on its ground floor and a club memorabilia collection and archive in its upper floor. Centrally located is an oculus, visually and volumetrically connecting the two floors. At its base is a round table intended for everyday use. A staircase situated between the walls of the oculus and the former factory exterior provides a physical and symbolic connection between different layers of the building’s history, echoing principles of continuity and transformation central to heritage discourse. Materially the oculus is clad in a terrazzo speckled with salvaged fragments of floor and wall tile, bricks, and concrete from the kitchen excavation.

Formally the oculus makes a solemn reference to the foibe—deep natural sinkholes in the Karstic limestone landscape surrounding Trieste, which became sites of mass killings during and after the Second World War arising from the conflicts between Italians, Slovenes, and Croats. These conflicts were among the driving forces of Triestine migration to Australia. The oculus through material and form facilitates encounters between histories recent and past, close and distant, observable and tacit. The outbuilding in its totality serves as a place of activity as well as memorial, acknowledging the complex histories that shape cultural identity.

Thirdly, the current car park in front of the building is restructured to become a garden. Receiving water through rain chains from the court canopy’s gutters, the spacing of the planting beds is contingent on former spatial references. The garden consists of four beds, capped with white pebbles, offering community gardening opportunities and spaces for reflection. The former entrance of the social club is disrupted with this scheme, becoming a pond shared between interior and exterior.

From the club’s interior, an echo of Trieste is constructed through the composition of a Karstic garden foregrounded by water. The now inaccessible passageway becomes a looking glass; part view and part veil.

This thesis explores the restructuring of the Trieste Social Club in Essendon, Melbourne, focusing on its role in preserving Triestine migrant identity. Italo-Australian social clubs, once essential social infrastructure for post-war migrants, now face challenges due to ageing populations and shifting identities.

To frame this exploration, I addressed two key research questions:

1. How does migration influence placemaking and the built environment, particularly in the context of Italo-Australian social clubs like the Trieste Social Club?

2. In what ways can the architecture of the Trieste Social Club reflect and facilitate the complex narratives of place-identity and identity politics among migrant communities?

Restructuring

The project introduces “restructuring” as a method distinct from adaptive reuse. While adaptive reuse repurposes buildings for new uses, restructuring favours the reinterpretation of material, programmatic, and compositional structures.

Through processes of excavation, evaluation, and stratification, the project aims to respect the club’s history while adapting it for contemporary needs. Through this approach, the Trieste Social Club can continue to serve as a centre for cultural production, supporting intergenerational connections and evolving demographics.

4 Willow Street, Essendon

The Trieste Social Club, established by immigrants from Trieste—a mitteleuropean city on the eastern edge of northern Italy—serves as a focal point for this investigation into migration, expressions of place-identity, nostalgia, and cultural heritage in the built environment. By restructuring rather than reusing, renovating, or restoring the site, its historical and cultural layers are kept relevant for contemporary and future needs.

Designed by architects Millar and Barnard-Brown in 1965, the building originally served as a textiles factory. Post-Second World War immigration saw the establishment of various social clubs to support Italian immigrants in Melbourne’s suburbs. The then-San Giusto Alabarda Social Club purchased this factory in 1978 and adapted it under the guidance of Trieste-born RMIT-trained architect Ermin Smrekar. A significant adaptation at this time was the infilling of the sawtooth volume with a vaulted structure, converting the expansive, light-filled factory floor into a ballroom.

Proposed Design

Aligned with these processes of excavation, evaluation, and stratification, the proposal consists of a series of interventions for the existing site - three in particular exemplify these distinct attitudes to space-time relations.

Firstly, I propose the creation of a bocce court. Extending into the building's facade this gesture displaces the existing kitchen, which is subsequently pivoted around the ground floor clubhouse and tucked into the building’s side. The court’s canopy sits atop columns spaced 4200 apart following structural and rhythmic cues from Millar & Barnard Brown’s building. These columns are covered in a basalt roughcast, a similar but different expression to the factory’s facade. The bocce court reflects the club’s Italo-Australian context while offering an intergenerational and casual recreational space for members and the broader neighbourhood. Its presence transforms the former interior walls of the social club’s kitchen into partial exterior and disrupts its new adjacencies. Upstairs a bar overlooks the court. Hosting kitchen tiles salvaged from behind plasterboard during excavation, the bar’s expression serves as material and perceptual reminders of spatial occupations past.

Secondly, an outbuilding extending from the facade’s west fosters moments of encounter and reflection. The outbuilding hosts a cafe on its ground floor and a club memorabilia collection and archive in its upper floor. Centrally located is an oculus, visually and volumetrically connecting the two floors. At its base is a round table intended for everyday use. A staircase situated between the walls of the oculus and the former factory exterior provides a physical and symbolic connection between different layers of the building’s history, echoing principles of continuity and transformation central to heritage discourse. Materially the oculus is clad in a terrazzo speckled with salvaged fragments of floor and wall tile, bricks, and concrete from the kitchen excavation.

Formally the oculus makes a solemn reference to the foibe—deep natural sinkholes in the Karstic limestone landscape surrounding Trieste, which became sites of mass killings during and after the Second World War arising from the conflicts between Italians, Slovenes, and Croats. These conflicts were among the driving forces of Triestine migration to Australia. The oculus through material and form facilitates encounters between histories recent and past, close and distant, observable and tacit. The outbuilding in its totality serves as a place of activity as well as memorial, acknowledging the complex histories that shape cultural identity.

Thirdly, the current car park in front of the building is restructured to become a garden. Receiving water through rain chains from the court canopy’s gutters, the spacing of the planting beds is contingent on former spatial references. The garden consists of four beds, capped with white pebbles, offering community gardening opportunities and spaces for reflection. The former entrance of the social club is disrupted with this scheme, becoming a pond shared between interior and exterior.

From the club’s interior, an echo of Trieste is constructed through the composition of a Karstic garden foregrounded by water. The now inaccessible passageway becomes a looking glass; part view and part veil.